7 min to read

The Indian Monsoon Story

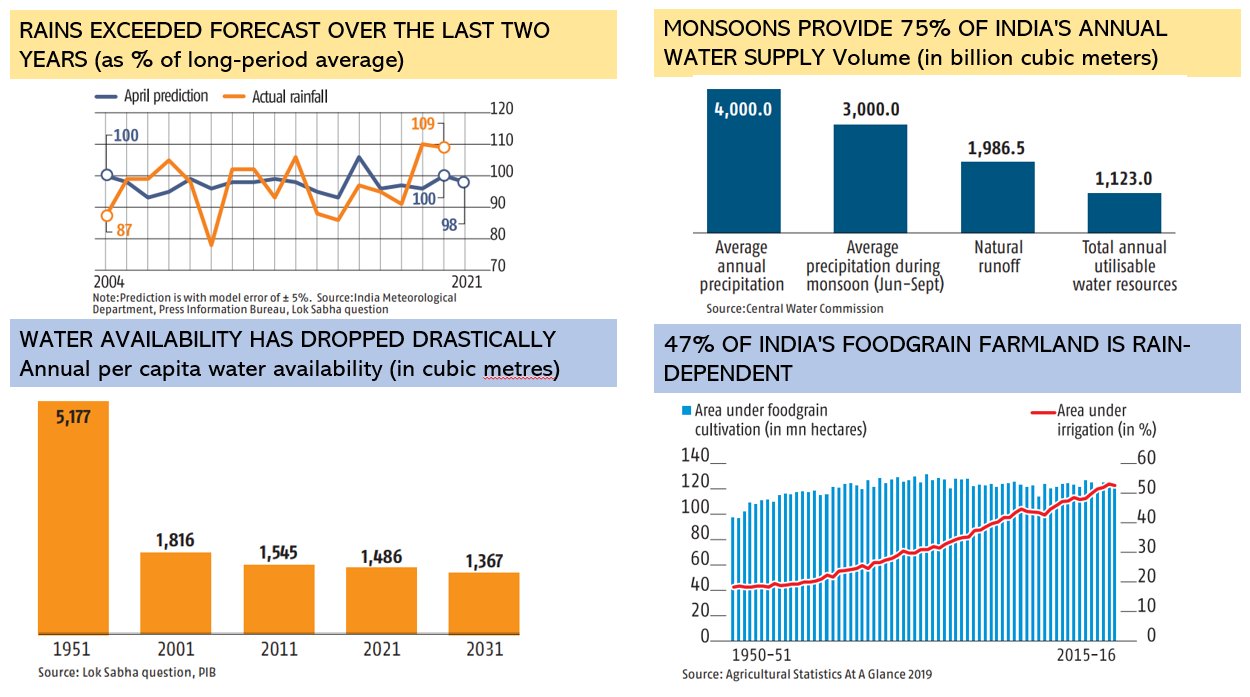

The monsoon delivers nearly 70% of the rain needed by farms, besides replenishing reservoirs and aquifers.

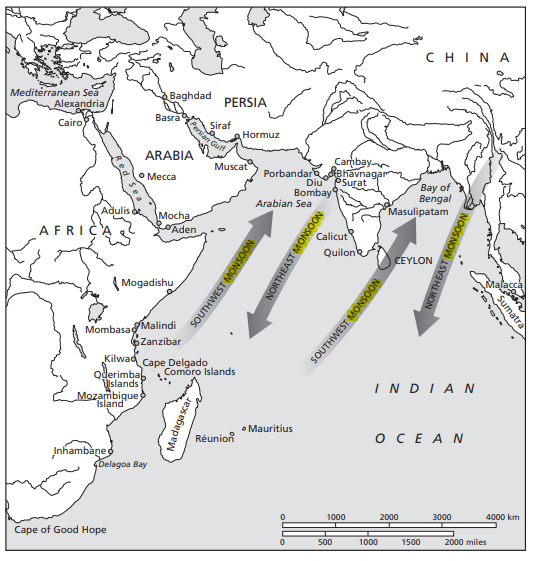

The monsoons are a door to the past, present and future of India. It carries the convergence of culture, ideas, movements, and concepts that made up a historic era, and was also a channel for cultural exchange with other parts of the world.

The History

Pliny the Elder labelled it Hippalus after the legendary sailor, but Roman and Greek never able to master these winds and related actions. Hence, it was left to Arabs to give it the Modern name. Word comes from Arabic mawsim, mausim, appropriately meaning ‘season, time of year’

It could have also come from another word-from wasama - ‘to mark’ and thus also meant ‘appropriate season (for a voyage, pilgrimage, etc.)’. For European traders, it was a new concept as they knew only summer, autumn, winter & spring. Then came Portuguese.

Portuguese sailors in the Indian Ocean discovered this Arabic word and started using it to indicate the season when the winds were just right to begin sailing towards the East Indies. The same was followed by Dutch traders and the word entered into English somewhere in 1584.

What is it all about?

The monsoon is the large-scale circulation of winds in the tropics. It comprises a reversal of direction in the trade winds from southwesterly to southeasterly. The wind shift typically occurs near the Equator between May and September. We know this pattern of change as the monsoonal circulation or the Indian Ocean dipole.

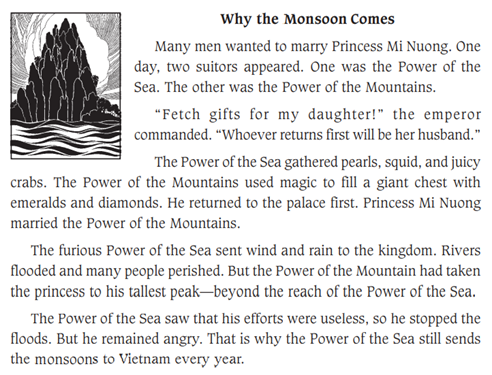

East India monsoon, also called the South Asian monsoon, brings the annual rainfall in South Asia. It is called Bayu in Indonesian and Malay to describe the local winds led by Kapalaran or Nabalar of Austronesian people. This tale from Vietnam offers an interesting explanation of a monsoon.

Legend has it that before leaving, Vasco Da Gama dares to ask the Zamorin of Calicut whether he may carry a pepper stalk back with him for replanting. While the Zamorin’s courtiers are outraged, the Zamorin calmly responds, ‘you can take our pepper, but you will never be able to take our rains.’

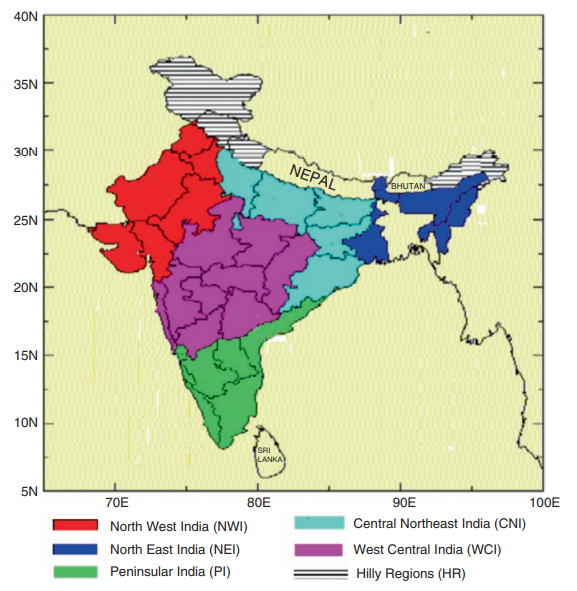

Monsoon regions of India.

But there is more than just rain involved. The three months that make up this season are critical for India’s economy as some 7–8% GDP comes from agriculture. The amount of our agricultural productivity relies on the Monsoons for a majority of India’s population.

Monsoon-dependent peninsular rivers that flowed out of the uplands of central and southern India provided an uncertain source of water. Canals in Punjab had rivers fed by snowmelt and part of UP was well served by Private wells. This shaped how these places will grow their crops.

Are you an Equity investor?

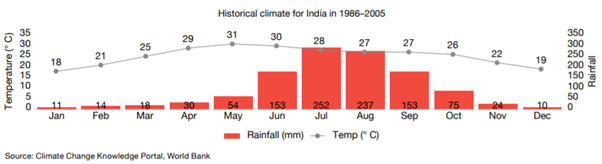

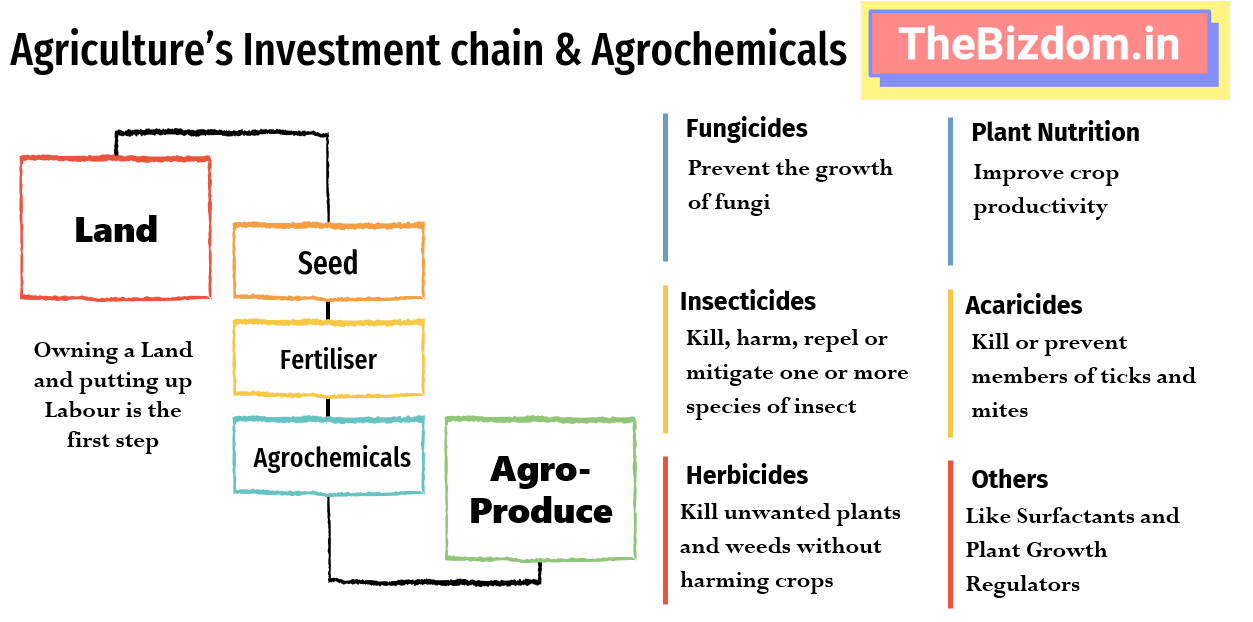

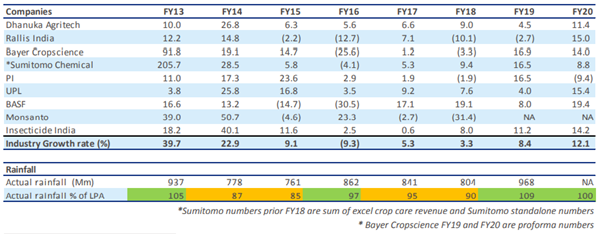

Now, let’s understand how it impacts us (and equity investors). First thing first, Poor rains potentially hurt the agricultural output and lead to food inflation. In India most of the agricultural activity starts just before the monsoon. So early June to the end of July is the initial planting season for most crops. Then August and September would be the growing time and probably early October might be the harvest for some crops. What this means for fertilizers, pesticides and insecticides companies is that a bulk of their revenues comes from June to September. So, in a good monsoon Q2 and Q3 can be good. Then Q4 and Q1 are not so good.

Rainfall is normal when= 96% -104% of the average rainfall of past 50 years

Roughly 50% of arable land is still not irrigated and 63% of irrigated land is dependent on tube wells, which are at the mercy of the monsoon; thus it provides an opportunity for agri pipes (mainly PVC) players in India.

Crops

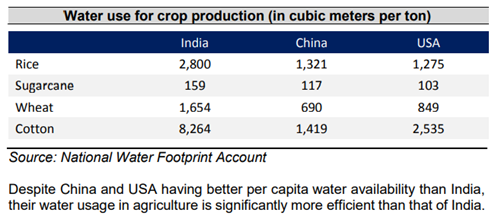

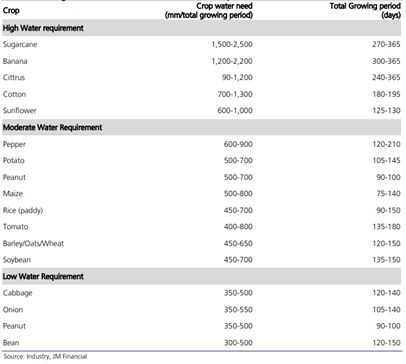

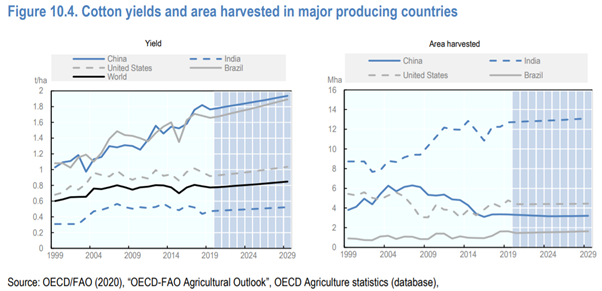

India is one of the largest producers of rice, sugar and cotton and the water consumption for these crops is significantly higher than global standards. Good monsoon is esp needed for Sugar and Cotton.

Let me explain in little detail.

UP has significant coverage of irrigation, so are less dependent on Monsoon. But for the other three states dependence on monsoon/reservoir situations is very high. Remember Sugar is a Water Sucking plant.

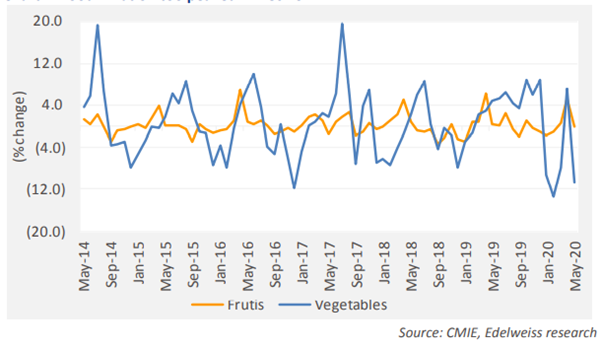

Fight Inflation and add demands

All this keep Food inflation under control and have positive impacts for many Food FMCG companies, in form of low Raw Materials. Good monsoons can lower milk price inflation (milk constitutes 45% of Nestle’s raw material cost). Then all this lead to good demands also. Let’s get back to some history for this.

By 1780s that Bombay began to replace Surat, and for that, a lot of migrants workers were needed at Dock. Most of these came from Coastal belt of Ratnagiri. Then, almost all of these used to returned to sow rice in time for the monsoon. They also used to spend their earning on the repairs to their homes in their native villages. This created the trends of expenditures on building materials and other discretionary expenses. In modern time, such expenses have to wait when Farmers get their payouts. But remember, all is well till its end well.

Since, heavy rains towards the end of the monsoon (late September) will have a detrimental impact on low rainfed crops like coarse cereals, vegetables and fruits.

Monsoons are thus a rainbow of hope for Indian agriculture and economy. The rural economy was a saving grace for India’s 2020 gross domestic product numbers, which saw a rare recession not led by an agricultural shock. So, again a to is expected from Our Monsoon this time again.

Pakora

The monsoon season is upon us. Rain, rain. Rain. What else is new? Oh wait! let’s talk about the things that are the most favorite when it rains in India and Pakistan. What better way to celebrate the monsoon than with a cup of hot tea and a plateful of spicy pakoras! Pakora is a savoury deep-fried cake containing bits of onion, potato, cauliflower, eggplant, or for that matter just any other vegetables. Chickpea is used to make flour, and as a batter to coat various vegetables. In north India, pakoras are sold standing in front of shops in plastic bags which you can hold with two hands while standing in rain, eating it.

Let’s pray for another good season of Barsaat!!