9 min to read

From ideology to modernity: The 30th anniversary of LPG

An event when the country shed decades of ideological baggage and socialist rhetoric.

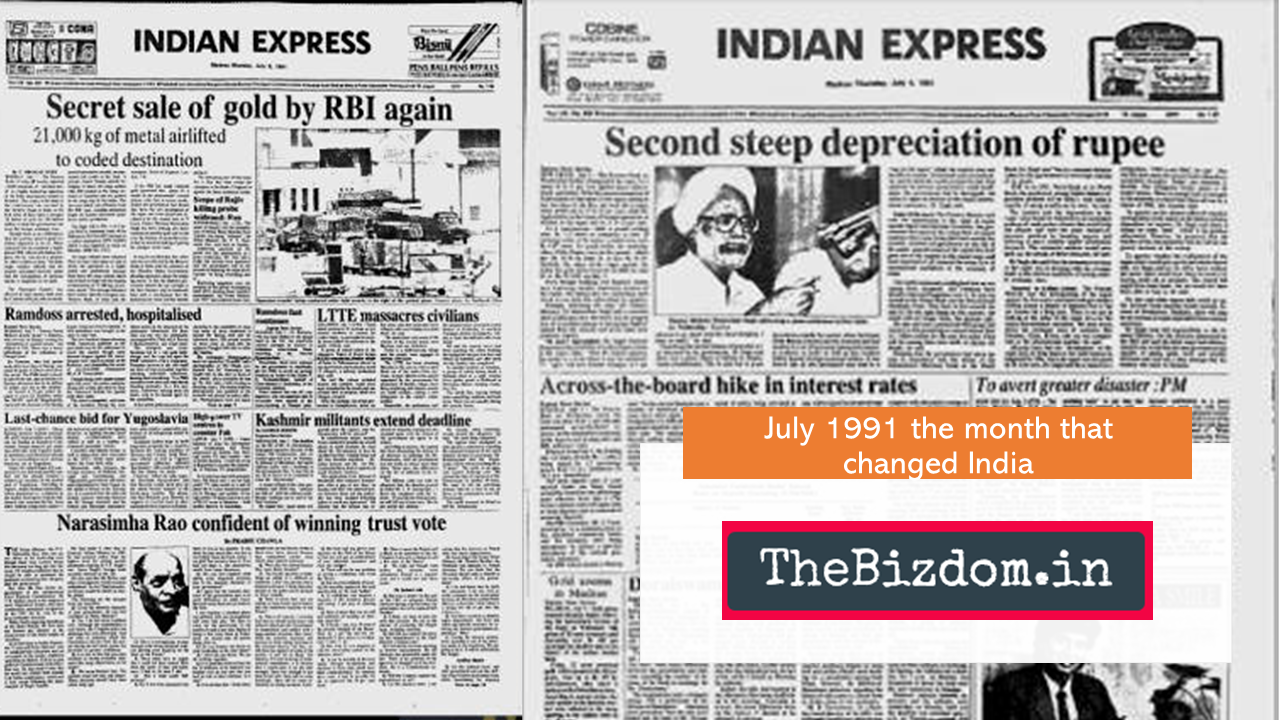

In May 1991, India had airlifted 20 tonnes of confiscated gold to Zurich to raise $240 million, but somehow news didn’t get its attention, but it did prepare the News reporters to follow the event. Later, on 4 July 1991 the Reserve Bank of India was again given the task of transporting 47 tonnes of gold to the Bank of England. Commercial airlines had excused themselves from the operation due to its excessive risk, which meant that Heavy Lifting Cargo Airlines had to be chartered to take the load to England in four stages. A high security convoy was first needed to transport the gold from the RBI’s vaults in South Bombay to Sahar Airport in the north of the city.

Since this was a second act, details of the gold lift, including a large picture of the plane being loaded with the precious metal, promptly made their way onto the pages of the Indian Express.

But Why are we sending these Gold?

It was Prime Minister Chandra Shekhar and Finance Minister Yashwant Sinha—on the advice of the RBI Governor S. Venkitaramanan—who first decided to use our gold reserves to raise foreign loans to keep the wheels of the economy moving. Under Nehruvian socialism, the economy had suffered for quite a long time.

The decade 1980–1 to 1990–1 was marked by the low growth syndrome of the Indian economy on the brink of defaulting on its debt in 1991, while the world around us was changing: Soviet Union was in perceptible economic decline, China had turned to the market and East Asia’s economic success was widely attributed to its free market policies.

However, the recent pressure on the reserves had come from the trebling of oil prices following the Gulf War of August 1990.

To make matters worse, India had to repatriate thousands of workers from Kuwait back home. Other issues were Political instability (by October 1990, the V.P. Singh government was tottering), that prompted non-resident Indians (NRIs)—whose deposits were a valuable source of dollar support to the economy—to start withdrawing their money from Indian banks. So, by June 21, 1991, when PV Narasimha Rao took over as Prime Minister, we had run out of our foreign reserves.

We only had $1.2 billion in reserves—just about enough to meet three weeks of imports. Monies were needed desperately, and the Indian government pledged 67 tonnes of gold to the Bank of England and the Union Bank of Switzerland to raise $605 million.

Those two months of 1991

21 May 1991 when Rajiv Gandhi was assassinated, and Congress needed a new leader. And, as a rarity Congress held an election to choose their leader. In which P V Narasimha Rao easily beat Sharad Pawar. Congress (I) had won 226 seats, 30 short of an overall majority, and formed a minority government.

20th June Narasimha Rao was elected leader of the Congress Parliamentary Party (CPP). he then invited Manmohan Singh, who was then the chairperson of the University Grants Commission, to become a Cabinet minister. Next day Mr. Rao took over as prime minister, and Manmohan Singh was the finance minister.

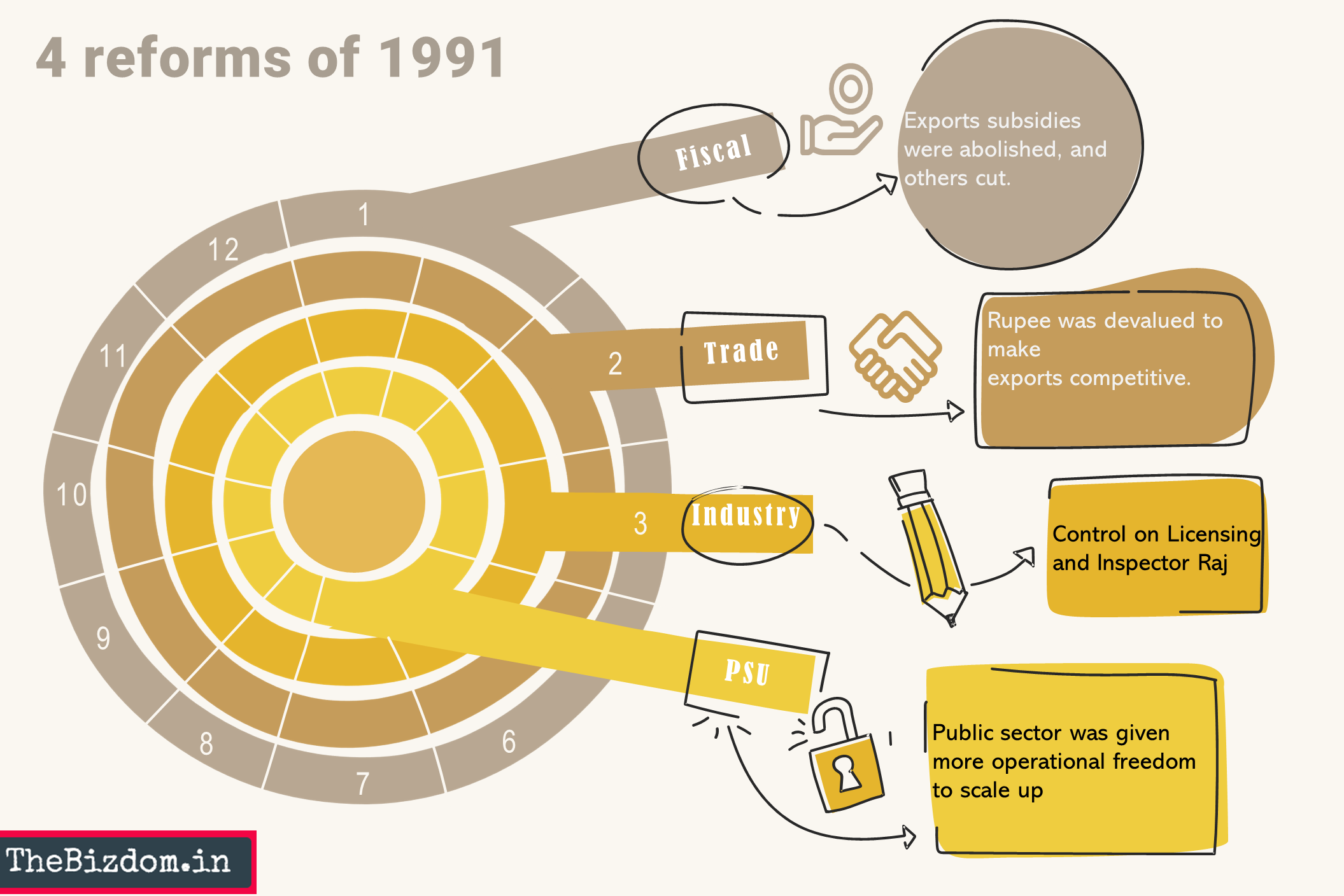

1st July the exchange rate of the rupee against major currencies was devalued by 7-9%. It was a two step exercise to test the water. This initial devaluation had little economic effect, only serving to stir political opposition from the Communist Parties and the Bharatiya Janata Party. Another slightly larger devaluation took place on 3rd July bringing the total devaluation of the rupee to 20% in two days.

4th July, changes in Trade Policy were discussed and on the same day, the West Bengal government released a document titled ‘Alternative Policy Approach to Resolve BoP Crisis’. In it, it called for an increase in income tax rates, cuts in non-development expenditure, the collection of tax arrears and the unearthing of black money.

7th July, Rakesh Mohan’s old draft for industry policy reform was ready for presentation in a new form. It recommended the abolition of all industrial licenses barring a small negative list. It is said that The prime minister leaked the document to the press himself.

7th July, Rakesh Mohan’s old draft for industry policy reform was ready for presentation in a new form. It recommended the abolition of all industrial licenses barring a small negative list. It is said that The prime minister leaked the document to the press himself.

9th July, Rao addressed the nation again on Doordarshan and over All India Radio on 9 July. He wanted to send political signals regarding his overall approach.

12th July, Kalyani Shankar published a story in The Hindustan Times titled “Industrial Licensing to Go”. The note on industrial policy was presented to Cabinet on 15 July 1991.

15 July 1991, the motion of confidence—moved three days earlier. was at his philosophical best

What have I done? What had the government done? We know that there are no alternatives to what we have done. We have only salvaged the prestige of this country. Sarvanashe samutpanne ardham tyajati panditah. This is precisely what we have done. I do not say that the economy has been booming or is going to boom immediately. What I am saying is sarvanashe samputpanne.

Left parties and those that made up the National Front (like the Janata Dal) decided to walk out. The BJP voted ‘no’, but was hopelessly outnumbered.

But then,the policy still faced more opposition within Congress, veterans like Arjun Singh were still not happy. But Rao was in no mood to stop. Later, Jairam Ramesh added a preamble honouring the foundational ideas of Jawaharlal Nehru and Indira Gandhi and the Cabinet accepted the note on 23 July. As, in his book-TO THE BRINK AND BACK, he said:

“I had a Sherpa’s role in the design of some of these changes, particularly as they related to industrial policy. This book is based on my own recollections, conversations with some key players in that drama, written records like parliament debates”.

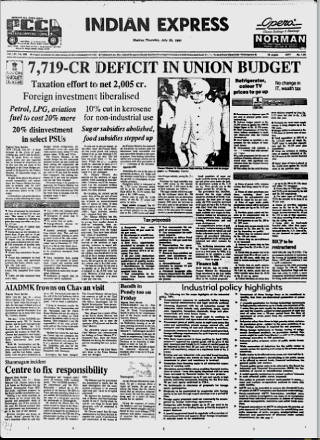

July 24: 11 am — New Industrial Policy Resolution; 5 pm — Budget for 1991-92

The Union Budget was to be presented on 24 July, yet before Manmohan Singh rose to speak, Narasimha Rao, in his capacity as commerce and industry minister had Pallath Joseph Kurien, his minister of state for industry announce the tabling of the new Industrial Policy. The Policy began with the statement: “Industrial licensing will henceforth be abolished for all industries, except those specified, irrespective of levels of investment.” Manmohan Singh started with:

The Union Budget was to be presented on 24 July, yet before Manmohan Singh rose to speak, Narasimha Rao, in his capacity as commerce and industry minister had Pallath Joseph Kurien, his minister of state for industry announce the tabling of the new Industrial Policy. The Policy began with the statement: “Industrial licensing will henceforth be abolished for all industries, except those specified, irrespective of levels of investment.” Manmohan Singh started with:

I do not minimise the difficulties that lie ahead on the long and arduous journey on which we have embarked. But as Victor Hugo once said, ‘No power on earth can stop an idea whose time has come.’ I suggest to this august House that the emergence of India as a major economic power in the world happens to be one such idea. Let the whole world hear it loud and clear. India is now wide awake. We shall prevail. We shall overcome. With these words, I commend the budget to this august House.

Post Events of LPG- Liberalization, Privatization, and Globalization

The Law of Laissez-faire is a term used by economists to describe a regulatory policy by which the government does not interfere with business and the free market system.

In the late 17th century, French minister under Louis XIV (the “Sun King”), Jean-Baptiste Colbert, once asked a group of businessmen what he could do for them. One of them, Legendre, replied, “Laissez nous faire”—leave us alone. Thus, rules were changed under Laissez faire, to leave things alone, and let goods pass through.

In the same manner, Manmohan Singh Union Budget overhauled India’s trading economy, doing away with import licences, announcing measures for export promotion and reducing tariffs. Capital markets were liberalised and subsidies were reduced on fertilisers, cooking gas and sugar. A $220 million loan had been received from the International Monetary Fund two days earlier. More loans were arranged in September and November, and January, February and March of 1992.

It was aimed for three possible after events

- The growth of private-sector participation and export orientation in the processing industries following delicensing, control over the source of feedstock to ensure quality and traceability became desirable.

- Consumpition growth: the emergence of supermarkets and modern retail chains necessitated a steady supply of fresh produce of consistently good quality

- Agri-reform: against a background of a silent collapse of state extension systems and rising input subsidies to agriculture, policy intervention was to create spaces for the private sector within agriculture. But, then the Contract farming didn’t last long.

But then cheaper rupee meant that Indian exports would become more competitive, making one of the export subsidies, the Cash Compensatory Scheme redundant. As mentioned on Twitter

To put Indian IT Services exports in perspective - at ~$170B it exceeds Saudi Arabia’s oil exports in value All in a matter of 30 years starting from scratch!

Economic Reform and Stock market Development

Liberalisation measures have included the repeal of the Capital Issues Control Act 1947 by which the government controlled new share issues and determined the issue price. Externally, liberalisation has allowed foreign institutional investors to directly purchase Indian corporate shares. The flagship of the government’s new regulations to ensure transparency and above board functioning of stock markets has been the Securities and Exchange Board of India Act which came into force in January 1992.

In 1980, the total market capitalisation on the Indian stock markets as a proportion of GDP was only 5%. By 1990, following the liberalisation measures initiated during the 1980s, the ratio rose to 13%. With the accelerated pace of liberalisation under Dr Singh’s reforms the stock market growth has been explosive. By end-1993, total market capitalisation reached 60% of GDP.

A lot more needs to change

The second wave of the pandemic may have receded a bit, but it is still upon us. We are on the brink of breakthroughs that will profoundly change the way we live, work, and relate to one another. India needs critical reforms in health, labor, land, skills and agriculture.